Here Are Some Of The Most Amazing Facts About Jellyfish

Amazing Facts About Jellyfish

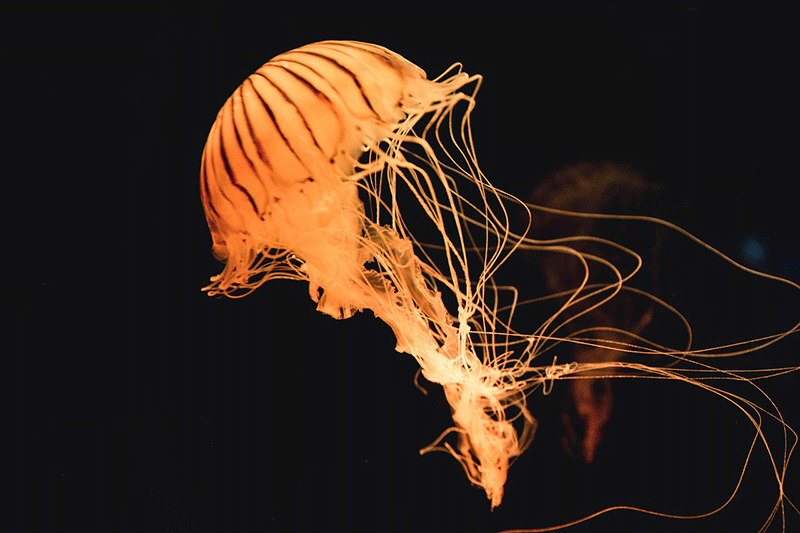

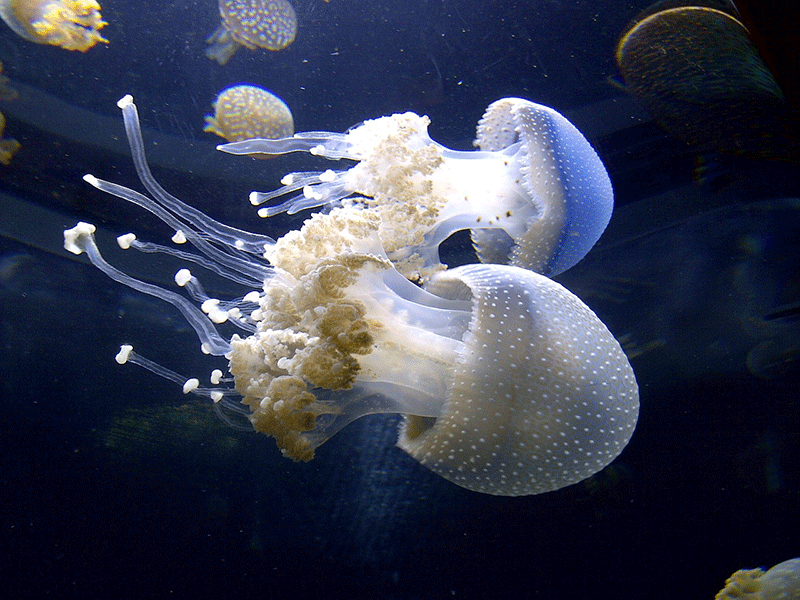

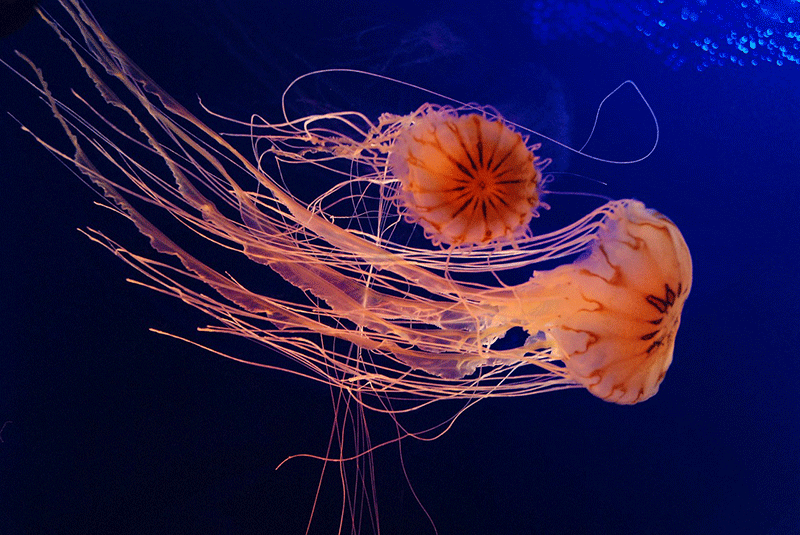

People think of jellyfish almost exclusively as pink-to-translucent type orbs with long tentacles, but jellyfish are one of the most varied species on the planet. Over 10,000 species of jellyfish populate our oceans and seas and most belong to the phylum Cnidaria. There are so many shapes, sizes, and genus of jellyfish, that marine biologists aren’t even sure the word “jellyfish” is appropriate…or even accurate.

Jellyfish aren’t just varied in every conceivable way. These mysterious tentacled-orbs predate humans by hundreds of millions of years. There’s evidence that they’ve been stalking Earth’s seas for at least 500 million years, but that timeline isn’t fixed. It’s also possible they’ve been floating about for over 700 million years. If it’s true, then they’re the oldest multi-organ animal group still occupying the water and even the Earth.

The diversity of these creatures means there’s plenty of amazing facts to go around. Are you ready to learn more?

It’s All About the Phylum: Cnidaria

Cnidaria is the phylum hosting most of the jellyfish, and its portfolio boasts over 10,000 species of freshwater and marine animals. Cnidarians sit in a middle ground of marine species: they’re more complex than sponges, but they don’t share the attributes of bilaterians, where most other marine animals find their home.

How are jellyfish more complex than sponges? Their complexity occurs some very important ways.

Unlike sponges, jellyfish have muscles and nervous systems. Their cells are also bound by connections and membranes. Some genus of jellyfish even boasts sensory organs.

These floating wonders differ from all animals in one important way: cnidocytes. Cnidocytes are an explosive cell that jellyfish use to capture fish and crustaceans they enjoy on for dinner. These little harpoons are unique to Cnidaria; no other animal phylum has them.

The One True Jellyfish: Scyphozoans

You’ll find what are called “jellyfish” in both fresh and salt water, but did you know there’s only one true jellyfish?

Scyphozoa live only in marine environments (salt water), and they’re referred to as “true jellies” or true jellyfish.

The word Scyphozoa is derived from a single Greek term: skyphos, which described the shape of a specific Greek drinking cup. The Skyphos cup is a deep bowl-shaped up featuring two handles. Scyphozoa feature a similar bowl-shaped body, but of course, they don’t feature handles or hold wine.

Jellyfish in the Scyphozoa taxonomic class are the largest out of all the jellyfish considered to be Cnidaria. They range from 0.79 to 15.78” in diameter and the Cyanea capillata, the largest species, grows to 6.6 feet in diameter.

Who are the false jellyfish? They’re Hydrozoa, which is derived from the Greek words hydra and zoon to create “sea animal.” Hydrozoa are small, predatory animals that live primarily in marine environments. These animals belong to the overall jellyfish phylum – Cnidaria – but not all Hydrozoa are jellyfish.

A few recognizable species fit into this taxonomic class, but most are freshwater jellies. These are small than the true jellyfish, and many don’t move freely.

Jellyfish Live Forever

The Cnidaria phylum has survived for as long as 700 million years on Earth. Its longevity isn’t lost on individual members: some jellyfish have what humans call “immortality.”

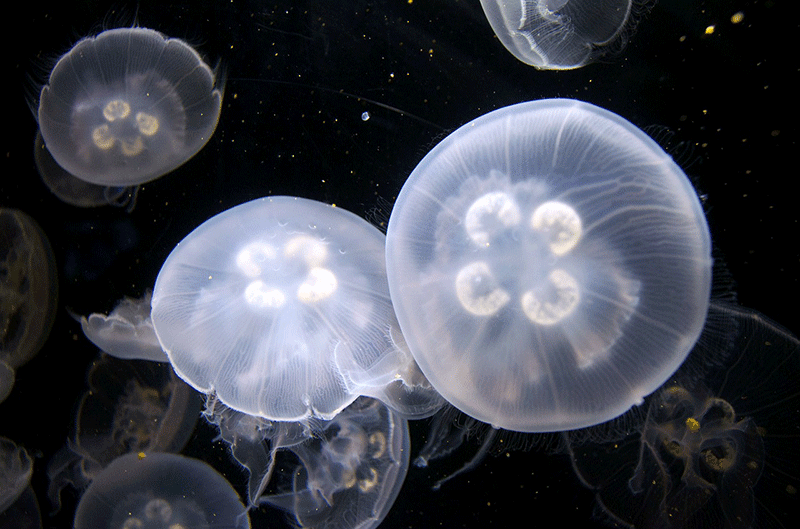

Turritopsis dohrnii are the best example of the immortal jellyfish. These bell-shaped jellies are very small and very thin – they reached a maximum diameter of 0.18 inches, which also happens to be their height. Although small, they are flashy. Their stomachs are red and feature a cross shape across the belly. A Turritopsis dornhii jellyfish’s body is also complemented by a surprising number of tentacles: while young jellies have eight tentacles, a mature specimen may grow as many as 80 or 90 tentacles.

It must be said: the average jellyfish has a fixed life-span, but not the Turritopsis dohrnii. Most jellyfish in the Hydra taxonomy feature a polyp stage responsible for asexual reproduction. These polyps create little clones which turn into little jellyfish. Here’s the difference: most jellyfish leave the polyp state and never return. When they reach the end of their lifespan, their cells and organs break down, and they die. The Turritopsis dohrnii goes through a special transformation process that allows them to return to the polyp state.

Why would a jellyfish want to live forever? It’s not clear that immortality is on the agenda. Scientists attempting to unravel the mystery find that these jellyfish revert from fully matured medusae into polyps only under specific conditions including:

When the medusa returns to its earliest form, the bell and tentacles deteriorate and break down. After all, polyps don’t need tentacles. If the medusa was already young and not fully formed, then turn into a cyst before turning into a polyp. Fully mature medusa may bypass the cyst stage and just turn into polyps.

The whole process takes just two days.

What does this mean?

Jellyfish avoid the changes to their environment that kill other animals because they’re able to hide away as polyps until conditions are favorable again. Eventually, these jellies move back through the maturation process to become stolons and medusas, but only after branching more stolons and polyps to create colonies.

The lifecycle described above is only what scientists saw in the lab. We have no idea how this happens in a jellyfish’s undisturbed natural environment.

While water temperatures, changes in salination, or lack of food may have killed off these jellyfishes’ neighbors 500 million years ago, it didn’t phase jellyfish who can wait until conditions are favorable.

The miraculous ability to reverse their life cycle is unique in the animal kingdom, but that doesn’t mean there are thousand-year-old jellyfish floating around the Mediterranean. The ability to return to polyps won’t save jellyfish from everything. After all, they’re still plankton and live their lives at the bottom of the food chain. Immortality won’t save them from being eaten by predators or disease.

Jellyfish Don’t Need Tentacles to Trap Food

Jellyfish are popularly known by two characteristics: their bell-shaped bodies and their tentacles. Tentacles seem critical to their identity. After all, these unlikely carnivores prefer to snack on other living sea life from little, defenseless plankton to crustaceans and even larger animals.

The infamous jellyfish sting is made possible through the tentacles. Every tentacle – and jellyfish have from eight to hundreds of tentacles – is covered in Cnidoblasts, the cells that contain stinging threads. Jellyfish have simple nervous systems and need to run straight into pretty to find it. When a jellyfish encounters a fish, plankton, or a person, the contact pressure on the tentacles pushes out the stinging threads, which send venom into the victim.

A jellyfish’s venom is toxic to most marine life, which kills them. Humans find it painful, but it won’t kill you. Larger cnidoblasts go deeper into your skin, which creates a more painful sting. Some jellyfish’s venom is also more toxic than others.

Basic reason suggests that without these tentacles, jellyfish won’t eat. But you’re wrong. One species of jellyfish don’t have tentacles at all.

The Deepstaria, which many people describe as looking more like a whale placenta than an animal, doesn’t have tentacles. So how does it defend itself? Or eat?

Both of the two known species of Deepstaria don’t sting their prey; they blanket them with their bodies. These jellyfish hang out until they run into something tasty and instead of stinging and poisoning them, they trap them and seal off their bodies to kill the plankton.

Your average jellyfish couldn’t accomplish this because it has a small bell that its tentacles compensate for. For Deepstaria, the opposite is true. A Deepstaria has a huge bell that acts like plastic bags, trapping and suffocating prey that dares to get too close.

Jellies Like Group Sports

How often do you see a lonely jellyfish? The answer is not very. A group of jellyfish is a swarm – or even a smack. If you’ve ever been stung by one of these watery creatures, you’ll appreciate the irony of its group name.

Jellies don’t worry about their direction in life; they go where the wind takes them, literally. When the wind or currents brings together a group jellies in a single area, they’re referred to as a swarm of jellies. But that’s not the only reason jellies might come together.

When you see an increase of jellies in an area that gathered as a result of reproduction, you’re looking at a bloom of jellyfish – not a smack.

Jellyfish aren’t just found in groups in the sea. Back in May of 1991, the Columbia shuttle took 2,478 moon jelly polyps into space to study the effects of gravity on mostly weightless creatures. The jellyfish born in space didn’t enjoy coming back to Earth. Perhaps they’d be called a vertigo of jellies.

Jellyfish Don’t Let Simplicity Stop Them

Jellyfish may be simple creatures that go where the currents take them and run face first into their food, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t some of the weirdest creatures in the sea – and in space.

What have you learned about jellyfish? Share your favorite amazing facts about jellyfish in the comments below.